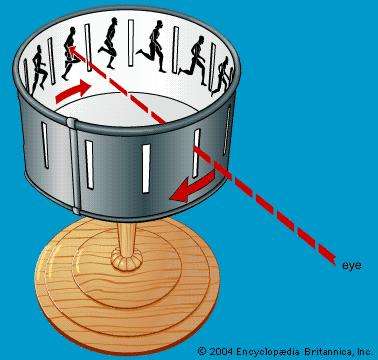

The theory of the animated cartoon preceded the invention of the cinema by half a century. Early experimenters, working to create conversation pieces for Victorian parlours or new sensations for the touring magic–lantern shows, which were a popular form of entertainment, discovered the principle of persistence of vision. If drawings of the stages of an action were shown in fast succession, the human eye would perceive them as a continuous movement. One of the first commercially successful devices, invented by the Belgian Joseph Plateau in 1832, was the phenakistoscope, a spinning cardboard disk that created the illusion of movement when viewed in a mirror. In 1834 William George Horner invented the zoetrope, a rotating drum lined by a band of pictures that could be changed. The Frenchman Emile Reynaud in 1876 adapted the principle into a form that could be projected before a theatrical audience. Reynaud became not only animation’s first entrepreneur but, with his gorgeously hand–painted ribbons of celluloid conveyed by a system of mirrors to a theatre screen, the first artist to give personality and warmth to his animated characters. With the invention of sprocket–driven film stock, animation was poised for a great leap forward.

The theory of the animated cartoon preceded the invention of the cinema by half a century. Early experimenters, working to create conversation pieces for Victorian parlours or new sensations for the touring magic–lantern shows, which were a popular form of entertainment, discovered the principle of persistence of vision. If drawings of the stages of an action were shown in fast succession, the human eye would perceive them as a continuous movement. One of the first commercially successful devices, invented by the Belgian Joseph Plateau in 1832, was the phenakistoscope, a spinning cardboard disk that created the illusion of movement when viewed in a mirror. In 1834 William George Horner invented the zoetrope, a rotating drum lined by a band of pictures that could be changed. The Frenchman Emile Reynaud in 1876 adapted the principle into a form that could be projected before a theatrical audience. Reynaud became not only animation’s first entrepreneur but, with his gorgeously hand–painted ribbons of celluloid conveyed by a system of mirrors to a theatre screen, the first artist to give personality and warmth to his animated characters. With the invention of sprocket–driven film stock, animation was poised for a great leap forward.

Although “firsts” of any kind are never easy to establish, the first film–based animator appears to be J. Stuart Blackton, whose Humorous Phases of Funny Faces in 1906 launched a successful series of animated films for New York’s pioneering Vitagraph Company. Later that year, Blackton also experimented with the stop–motion technique–in which objects are photographed, then repositioned and photographed again–for his short film Haunted Hotel. In France, Emile Cohl was developing a form of animation similar to Blackton’s, though Cohl used relatively crude stick figures rather than Blackton’s ambitious newspaper–style cartoons. Coinciding with the rise in popularity of the Sunday comic sections of the new tabloid newspapers, the nascent animation industry recruited the talents of many of the best–known artists, including Rube Goldberg, Bud Fisher (creator of Mutt and Jeff) and George Herriman (creator of Krazy Kat), but most soon tired of the fatiguing animation process and left the actual production work to others.

The one great exception among these early illustrators–turned–animators was Winsor McCay, whose elegant, surreal Little Nemo in Slumberland and Dream of the Rarebit Fiend remain pinnacles of comic–strip art. McCay created a hand–coloured short film of Little Nemo for use during his vaudeville act in 1911, but it was Gertie the Dinosaur, created for McCay’s 1914 tour, that transformed the art. McCay’s superb draftsmanship, fluid sense of movement, and great feeling for character gave viewers an animated creature who seemed to have a personality, a presence, and a life of her own. The first cartoon star had been born. McCay made several other extraordinary films, including a re–creation of The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918), but it was left to Pat Sullivan to extend McCay’s discoveries. An Australian–born cartoonist who opened a studio in New York City, Sullivan recognized the great talent of a young animator named Otto Messmer, one of whose casually invented characters–a wily black cat named Felix–was made into the star of a series of immensely popular one–reelers. Designed by Messmer for maximum flexibility and facial expressiveness, the round–headed, big–eyed Felix quickly became the standard model for cartoon characters: a rubber ball on legs who required a minimum of effort to draw and could be kept in constant motion.